As my mindset grew stricter around what I could—or rather, could not—consume, I became more creative at finding loopholes around these limitations. Ironically, baking became one of my favorite hobbies. However, this passion came with a significant caveat: I would never allow myself to taste anything I made.

Cupcakes, cakes, macarons—I enthusiastically baked them all, but solely for others. The idea of actually taking a single bite of any of these treats myself was unthinkable. Over time, baking became an obsessive daily ritual, batch after batch. It was my indirect way of engaging with food—a workaround that overcompensated for my desire to interact with it, without breaking the strict rules dictated by my eating disorder.

Understandably, my loved ones grew concerned. They couldn’t ignore the contradiction: I was constantly baking but adamantly refusing to eat anything myself. When approached, I deflected their concerns, insisting that I simply enjoyed baking for others and framing it as an act of generosity.

But deep down, I knew that if I ever dared to eat something I baked, the guilt and shame would be unbearable—often triggering panic attacks. Still, in the beginning, anorexia blinded me to the irony behind my baking hobby. It pulled me deeper into its world, convincing me I was in control. I was even proud of my so-called self-discipline.

“How disciplined I am,” I told myself, “to bake countless desserts without taking a single bite.” But in reality, it wasn’t my self-discipline on display—it was the eating disorder’s. Baking had become a ritual that fed the eating disorder’s grip and validated its rules.

The Psychology Behind Baking Without Eating

As anorexia is often driven by an overwhelming need for control, research sheds light on how preparing food for others allows individuals to manage their environment without consuming calories themselves (Fassihi, 2023). Much like my personal experience, many report taking pride in their perceived self-discipline and may even feel a sense of superiority in resisting food while watching others indulge (ERIC, 2018).

Cooking for others reinforces this sense of control and bolsters self-esteem tied to willpower and restraint. From a neurobiological perspective, anorexia also disrupts normal reward responses to food. Hunger fails to activate typical reward circuits in the brain (Kaye et al., 2023). Instead, eating provokes anxiety rather than pleasure. Engaging with food through preparation—or by watching others eat—becomes a safer, less triggering way to interact with food (Kaye et al., 2023; Fassihi, 2023).

Additionally, studies show that individuals with anorexia frequently displace their hunger onto others. Feeding or observing others eat can provide vicarious satisfaction—essentially “eating by proxy” (Fassihi, 2023). This behavior can temporarily soothe the biological drive to eat by offering substitute gratification—through the process of cooking, the smell of food, or watching someone else enjoy it—without having to confront the anxiety that comes with actual consumption (Eating Disorder Therapy LA, 2020; ERIC, 2018).

A Recognized Symptom and Path to Recovery

From a clinical perspective, excessive baking or cooking without eating is now recognized as a symptom of anorexia—a manifestation of the disorder’s internal conflict: a deep preoccupation with food, coupled with a profound fear of consuming it (Eating Disorder Hope, 2020; Rosewood Ranch, 2021). These behaviors provide comfort and control, while allowing individuals to avoid directly facing their fear around eating (National Alliance for Eating Disorders, 2021).

In treatment settings, this fixation is addressed with care and intention. Nutritional rehabilitation often begins by disrupting these patterns—sometimes by temporarily limiting food preparation for others (Eating Disorder Hope, 2020). Therapy then works to uncover the core beliefs driving the compulsion, helping individuals reframe distorted ideas about control and discipline. Through interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and exposure-based approaches, individuals can begin to build a more balanced and compassionate relationship with food (Fassihi, 2023).

When I reflect on the mindset I was in—the culmination of thought patterns that led to my baking obsession—and how research validates that experience, I realize how crucial it is to recognize these specific signs. These subtler forms of overcompensating—like excessive baking or cooking without eating—can be just as important to identify as the more visible symptoms. Early recognition of such symptoms can lead to timely intervention, more effective treatment, and a stronger chance at recovery.

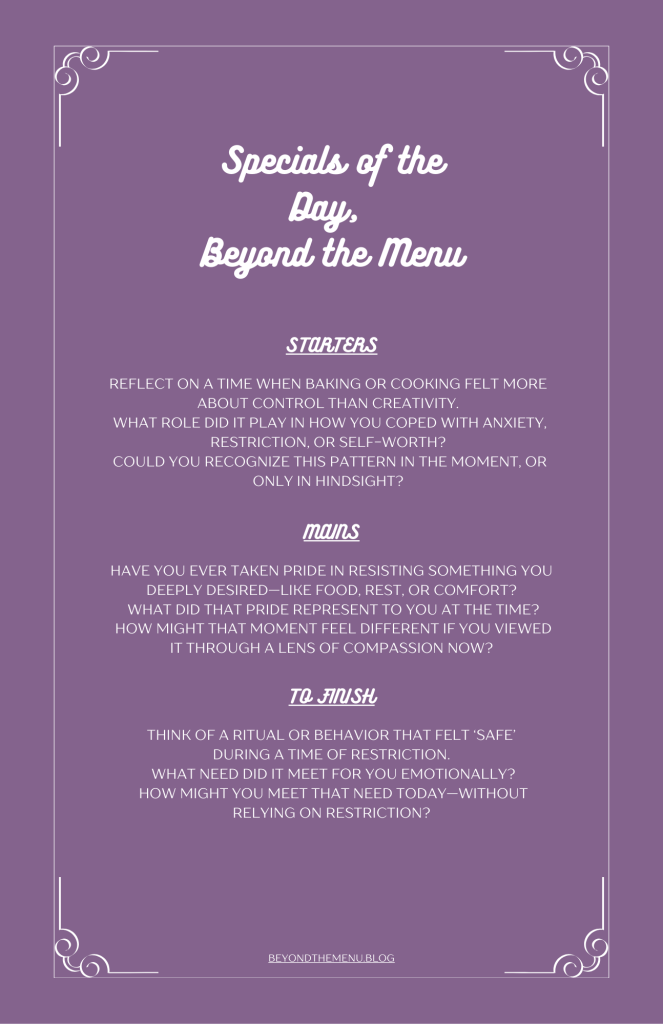

Specials of the Day, Beyond the Menu

Today’s Specials of the Day, Beyond the Menu, offer a gentle invitation to reflect on how overcompensation—like baking without eating—can quietly mask deeper emotional struggles. With time, awareness, and support, we can begin to reclaim self-trust, nourishment, and compassion.

Image description: Purple graphic with three journal prompts related to baking, control, and emotional safety during restriction.

References:

Eating Disorder Hope. (2020). Understanding starvation responses in anorexia nervosa. https://www.eatingdisorderhope.com

Eating Disorder Therapy LA. (2020). Anorexia nervosa behaviors and signs. https://www.eatingdisordertherapyla.com

Educational Resources Information Center. (2018). Recognizing anorexia: Symptoms and behaviors. https://files.eric.ed.gov

Fassihi, M. (2023). Why people with eating disorders cook for others. Psych Central. https://psychcentral.com

Kaye, W. H., Wierenga, C. E., Bailer, U. F., Simmons, A. N., & Bischoff-Grethe, A. (2023). Anorexia nervosa and brain reward systems. UC San Diego News. https://today.ucsd.edu

National Alliance for Eating Disorders. (2021). Warning signs and symptoms of eating disorders. https://allianceforeatingdisorders.com

Rosewood Ranch. (2021). Anorexia nervosa treatment: Understanding behaviors. https://rosewoodranch.com

Leave a comment